Source: Manatsa: From rags to riches, to enduring legacy | The Herald

Elliot Ziwira Senior Writer

The book on Zimbabwean popular music may still be out with the printers awaiting a grand launch on a date yet to be announced, but its contents exist in human memory as a complete version of what it means to dance one’s sorrows away on the stage of life, and from its pages leaps out the nightmarish and heart-rending story of Zexie Manatsa.

It is a rags to riches fairytale that awfully ends with a return to tatters.

In this unprinted book, characters have been known to thrive, hang on to hope and defy odds even, but very few have had their dance with fortune end as tragically as did Manatsa’s.

“My friend, there is nobody who could tell me what I don’t know about the world and its troubles,” the yesteryear legend opened up in an interview with The Sunday Mail in May 1995.

“I have been an active actor on its stage; I have been there and I can tell you all about it.”

Indeed, the deck of life deals cards randomly; making every hand a winner, and every hand equally a loser, but to Manatsa it appeared that the dealer conspired with fate to drop only losing cards onto his lap.

But it hasn’t always been like that, for at some point in his musical journey he used to bogey with Lady Fortune as a willing partner for life.

With a stormy career spanning over six decades, Manatsa has been described as a phoenix, doyen of satire, unsung hero and unifier capable of using a combination of strumming fingers, illuminating stage presence, booming voice and infectious smile to therapeutically touch hearts as music is wont to, even in a few seemingly simple lines.

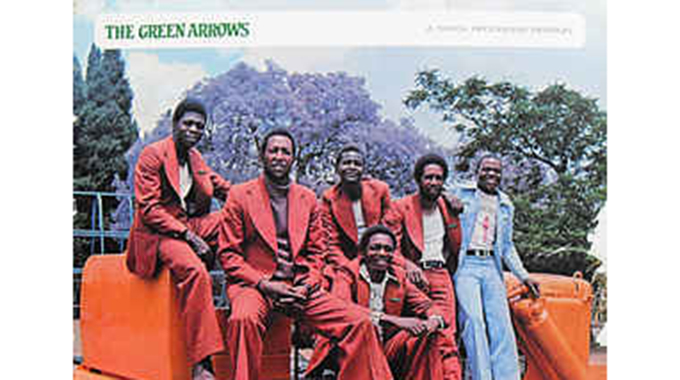

Manatsa, who died of cancer on Thursday aged 78, loved music, lived music, slept and dreamt music, to the extent that he named three of his sons, Green, Aaron and Benjamin, after the Green Arrows, the band that gave him fame, honour, love and, at some point, fortune.

His star could have shone forever brightly starting from his formative years in the late 1950s through the 1960s to 1974 when he made a musical breakthrough with the chart-topping song “Chipo Chiroorwa”, but ill-fortune seemed to be lurking in the green woods of the yesteryear legend’s success.

Lady Fortune knew Manatsa’s address and visited him often, but the world appealed to him more.

“During my worldly activities, I bought houses and cars for girlfriends. But today it’s just my wife and my five children; that’s all I have,” he told The Sunday Mail in 1995, adding, “I could have been a millionaire.”

Earlier on, in December 1991, he told The Sunday Mail Magazine, “I always thank God and my ancestors for keeping me alive.

“I am not bitter about anything; that’s how life goes. I had nearly everything, but I have lost everything.”

But what really went wrong?

How it all began

Like all fairy tales, Zexie Manatsa’s story began with lack, a dream and an illuminating halo from beyond the clouds with a voice imploring him to conquer his fears.

Born in the Doma Tribal Trust Lands near Sipolilo (Guruve) on January 1, 1944, the legendary crooner’s highest level of formal education was Standard Two (Grade Four).

At a time when musicians were considered societal misfits, beggars and scoundrels, Manatsa, then aged eight and attending school in Mhangura (then Mangula), armed himself with a banjo and dared the gods of music.

With the musical bug nagging him nonstop, he and his brother Stanley formed the group Spring Mambo, while still at Mangula Mine School. Alongside their friend, Jealous Siyagwanja, they would perform at “tea parties”, which were in vogue then, in beerhalls around the mine and its vicinity as well as other venues in Mhangura.

They did not have instruments of their own then, which exposed them to unscrupulous businesspeople.

In pursuit of the hornbill’s call, and fed up of being used, the brothers headed for Harare (Salisbury), where they briefly perform as the Mambo Jazz Band.

The Muse would later lead Zexie and Stanley to Bulawayo where the former bought a guitar for $75 before they joined Sunrise Kwela Kings, home to a motley of stars, the likes of Fanyana Dube, converged.

The year 1969 saw the brothers getting instruments from their uncle Homela, and the Green Arrows Band was formed. The band would later sign a contract with Happy Valley Hotel in Bulawayo.

Zexie, who started off as a tobacco picker at a farm in Mhangura, would later take up a job as a driver since they did not make enough to live on as musicians. He, however, could not keep the job for long as the stage beckoned him.

The Green Arrows’ breakthrough came in 1974 when the group recorded its first hit “Chipo Chiroorwa”, which was inspired by the wedding of Manatsa’s cousin, Chipo.

They had teased the discerning ear of Gallo Records’ scout, West Nkosi. Gallo would later release “Chipo Chiroorwa” as an album in February 1975.

In just three refrains, “Chipo Chiroorwa Tipemberere”, “Vabereki vedu vangazofare” and Tidye makeke titambe muchato, Manatsa, the song became an anthem in public places, homes and social gatherings from its release in 1975 to the early 1980s.

The record a won gold disc after selling 25 000 copies, making the Green Arrows the first African band to achieve the feat in Zimbabwe.

“Mwana Waenda”, and “Musoro Wanzomba” also won gold discs

By 1979, the group had released 36 seven singles and two albums, with “Mwana Waenda”, and “Musoro Wanzomba” also winning gold discs.

The satirist’s waka-waka crazy

Although some yesteryear music critics maintained that Manatsa’s lyrics fell short of the prolific nature of his music, the Green Arrows’ Waka-Waka genre endured as it circumvented the limitations of a purely local beat and imported genres.

Like a cartoonist, with his economy of words, power of caricature, and depth of foresight, he captures societal woes, expectations and glee; social political or economic, in a unique way.

Words are limiting, Manatsa realised earlier on in his career, in that they mean little if they are neither heard nor understood, thus he resorted to satire.

Leaning heavily on satire, Manatsa is able to poke at the follies and inherent in Man using something in between, a kind of waka-waka, popularised by Stanley unusual strumming of the guitar.

“Waka-Waka mixes local traditional music with other music trends from countries surrounding us,” he said in 1983.

Manatsa’s music borrows from all angles; mixing simanjemanje,

As a social commentator, the music icon uses tones of the satirist spectrum; wit, ridicule, sarcasm, cynicism and irony, to generate humour and give humanity a chance to laugh at itself.

Songs such as “Antonyo”, “Tiyi Hobvu” and “Vakaita Musangano” earned Manatsa the tag of a controversy, as they were said to mock white-garment apostolic sects, and deride foreigners in their struggle to speak Shona.

However, the legendary musician refuted such assertions.

“Some people might think I am mocking some social sects with “Antonyo but I am not. I am just commending on our social life to make people laugh,” the songster told The Herald in July 1983.

“People have complained that I discriminated against some religious sects when I sang “Vakaita Musangano” and “Tiyi Hobvu”, but that is not so.”

A rock ‘n’ roll wedding

It was dubbed the “biggest, happiest wedding of the year”, when the music icon tied the knot with Stella Katehwe on August 25, 1979 at Harare’s Rufaro Stadium.

It was a rock ‘n’ roll affair, combining a wedding reception and a musical concert, which left a 3 000 dollar dent in Zexie’s pocket, and attracted a paying audience of about 9 000 people, according to the Sunday Mail issue of August 26, 1979.

The wedding party was held from 10.30am to 5.30pm, with the bride and groom arriving at 3.45pm, from their wedding ceremony, in an 11-car convoy, and strutted hand-in-hand around the stadium led by high-stepping drum majorettes, much to the delirium of the roaring crowd.

“I have spent more than 3 000 dollars to organise this wedding, and have hired buses to carry people from various townships in Salisbury. There will be a special stage, with two trailers joined together,” Manatsa, who was expecting about 10 000 people at the reception, said in an interview in August 1979.

The who-is-who of Salisbury’s (Harare) musical scene, were invited to celebrate the wedding.

The bands in attendance were: Thomas Mapfumo and Blacks Unlimited, Oliver Mutukudzi and Black Spirits, Tineyi Chikupo and The Mother Band, Doctor Footswitch, The Search Brothers, OK Success Band, The Happening, Okavango Boys, Orange Juice, Jordan Chataika and Green Arrows Band.

During the concert, preceded by a Teal Disco between 10.30pm and 12pm, was opened by Thomas Mapfumo and his group, followed by the Green Arrows.

At least 300 fans grabbed free copies thrown into the crown by Manatsa, Mapfumo and Tineyi Chikupo, who each threw 100 of their group’s seven single records.

The wedding reception earned Manatsa and his bride $19 000 from gate takings, a substantial amount then.

Green, a family affair

Zexie and Stella were blessed with six sons, Green, Aaron, Benjamin (Tendai), Freedom, Shingirai and Takunda.

The six boys became part of the Green Arrows Band and later the Gospel Arrows.

But why Green for a name?

“Those were the days of the Green Arrows Band, my brother. The Green Arrows were a big thing; it was part of my life—so I named my first three boys Green, Aaron (for Arrows) and Benjamin (for Band),” he said in interview in 2005.

“And there was a time when I wanted to call them for tea, if they were playing outside, I would just yell, ‘the Green Arrows Band, come for tea.’ Little did we know that one day they will turn out to be the real Green Arrows,” Stella weighed in.

Fall from grace

A series of misfortunes saw Manatsa’s star waning in the late 1980s to early 1990s.

In 1984, Manatsa lost his musical instruments when his truck was involved in an accident in 1984 between Mutare and Beitbridge.

He was again involved in another near-fatal accident in September 12,1987 on his way from a show at Rusununguko in Chitungwiza around 2am, which left him in a coma for three weeks and hospitalised three months.

His doctor pointed out that it would take him five years to get back to normal activities since his brain was extensively damaged.

Manatsa maintained that misfortunes trailed him the moment he built a general dealer shop and bottle store in his rural home of Guruve in 1987.

A traditionalist then, Manatsa had just come from Guruve where he had sacrificed a bull and brew traditional beer in preparation for the grand opening of the business.

“I was confident that I did the right thing and I hoped that my ancestors would bless me in this business venture,” he said in a radio interview.

In a space of four years, between 1990 and 1994, he would also lose his brothers Stanley and Sebastian, who were key members of the Green Arrows.

In 1992, Manatsa was convicted of shoplifting hair dye worth $11,63 and fined $150 by a Kadoma court (or a month is jail).

Shunned by friend, his house repossessed, deserted by the musical gods and broke, Manatsa took to the bottle, and later turned to God in 1994.

An unsung hero

Manatsa and his Green Arrows contributed immensely to the politicisation and mobilisation of the masses during Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle through his music.

Although his political messages were subtle, Manatsa was arrested by the Rhodesian police when the Green Arrows was performing at Jamaica Inn along the Harare-Mutare Road.

“The whole group was arrested and beaten up by the police, and that is when we made a resolve to continue singing revolutionary songs,” he told The Voice Leisure and Entertainment in 2007.

“We mixed political songs with other entertaining tracks during our shows and we had to hide the meanings of the messages to avoid detection by the authorities.”

This inspired the release of hits such as “Nyoka Yendara”, “Pachaita Musangano” “Hama Dzedu Dzapera” and “Musango Mune Hangaiwa”.

Manatsa, who suffered persecution at the hands of the Rhodesian regime many times owing to his political songs, was part of the ZANU PF campaign trail leading to Zimbabwe’s first democratic elections in February 1980.

He would also offer his microphones and other gadgets for use at the rallies addressed by the late national hero and former President Robert Mugabe.

COMMENTS