Source: Just as in 1980, Zimbabwe’s Celebration May Be Short-Lived – The New York Times

By the thousands upon thousands, the people thronged the streets, waving banners, chanting slogans. A long-awaited future was fast approaching their land, Zimbabwe. One name was on all their lips: Robert Mugabe.

But this was not the huge crowd that flowed through Harare, the country’s capital, on Saturday, clamoring for Mr. Mugabe and his wife, Grace, to go. It was a jubilant crowd of 150,000 that welcomed Mr. Mugabe as a hero from his headquarters-in-exile in neighboring Mozambique in January 1980.

His return came at the start of a roller-coaster transition from white minority rule in Britain’s last African colony to an independent Zimbabwe.

In the weeks that followed his return, Mr. Mugabe survived assassination attempts, threatened to walk away from the peace deal reached under British auspices in London in late 1979 and won a landslide victory in elections that paved the way for independence on April 18, 1980.

On that night, working for the Reuters news agency, I stood with an open telephone line, ready to announce Zimbabwe’s birth on the stroke of midnight at a ceremony in Rufaro Stadium serenaded by Bob Marley and the Wailers. Prince Charles, the heir to the British throne, was among the foreign dignitaries in attendance.

The pageantry ended an era that began in 1890, when the first colonial settlers arrived in the so-called Pioneer Column to take over farmland and prospect for gold and other mineral riches. They gave the country new borders and a new name, Rhodesia, for Cecil John Rhodes, the British arch-colonialist. Some arrived in such expectation of riches that they called it Africa’s El Dorado.

In Rufaro Stadium, in April 1980, it seemed that colonialism’s tenure had been brief indeed. A hint of tear gas wafted over a wall from some indistinct encounter outside the stadium. Inside, the Union flag of Britain was furled and a band played “God Save the Queen.” The new Zimbabwean banner caught briefly on the flagpole, delaying freedom for a few seconds. But the moment of joy could not be denied.

I recall driving with a colleague — both of us white — through poor areas populated mainly by Zimbabweans who had little to thank white people for beyond menial jobs. Yet everywhere we were welcomed, embraced and invited to quaff chibuku, a sorghum beer popular among the less affluent.

The jubilation and the sense of renewal that suffused Zimbabwe in 1980 dissipated during the 37 years of Mr. Mugabe’s uninterrupted and increasingly despotic rule. But those same ardent passions resurfaced powerfully over the weekend, inspired by the clamor for Mr. Mugabe to go — as if the country had drawn a parabola beginning and ending in hope but passing on its course through violence, oppression and impoverishment.

Looking back, should the clues to what was to come have been visible as a subplot, at least, to the rejoicing? And what omens might they offer for a post-Mugabe era?

As a white resident of Harare, the first months of independence were a honeymoon, offered by Mr. Mugabe in gestures of reconciliation from a leader who had not wanted the war to end until he could claim a military victory.

But for the Ndebele people in the country’s southwest, the moment of harmony was short-lived. One of Mr. Mugabe’s first decisive political moves was to crush resistance among the Ndebele minority and to marginalize its leader, Joshua Nkomo, an erstwhile ally who had once seemed to be the patriarch of the struggle.

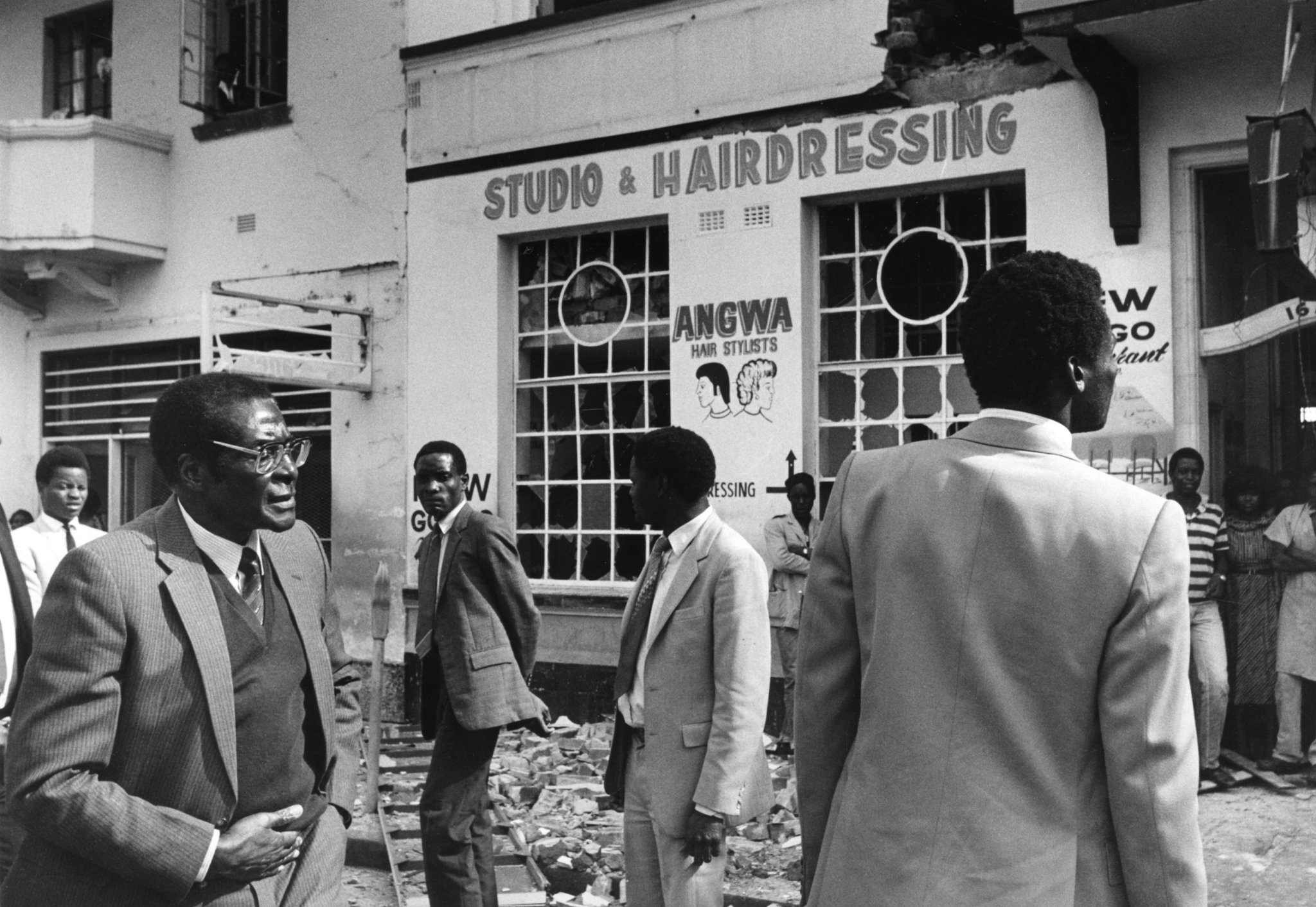

Mr. Mugabe outside the headquarters of the African National Congress in Harare in May 1986, after it was heavily damaged in a raid by South African commandos. CreditVictoria Kaufman/Associated Press

I remember ducking for cover in November 1980 as former guerrillas from Mr. Nkomo’s and Mr. Mugabe’s liberation armies traded fire in Entumbane, a township outside Bulawayo. Infinitely worse was to come, when Mr. Mugabe sent the North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade into Matabeleland, Mr. Nkomo’s heartland, to crush dissent. At least 10,000 people died, most of them civilians.

According to Wilf Mbanga, the editor of the weekly The Zimbabwean, Emmerson Mnangagwa, who replaced Mr. Mugabe as head of ZANU-PF on Sunday, and who is set to succeed him as president, was in charge of the intelligence services at the time of the massacres.

Mr. Mnangagwa “honed Zimbabwe’s ever-watchful Central Intelligence Organization into an elite dirty tricks team feared throughout the land,” Mr. Mbanga wrote in The Guardian. “Over the years, like his master Mugabe, he has been accused of masterminding election violence, kidnappings, extortion, plundering national resources and other crimes.”

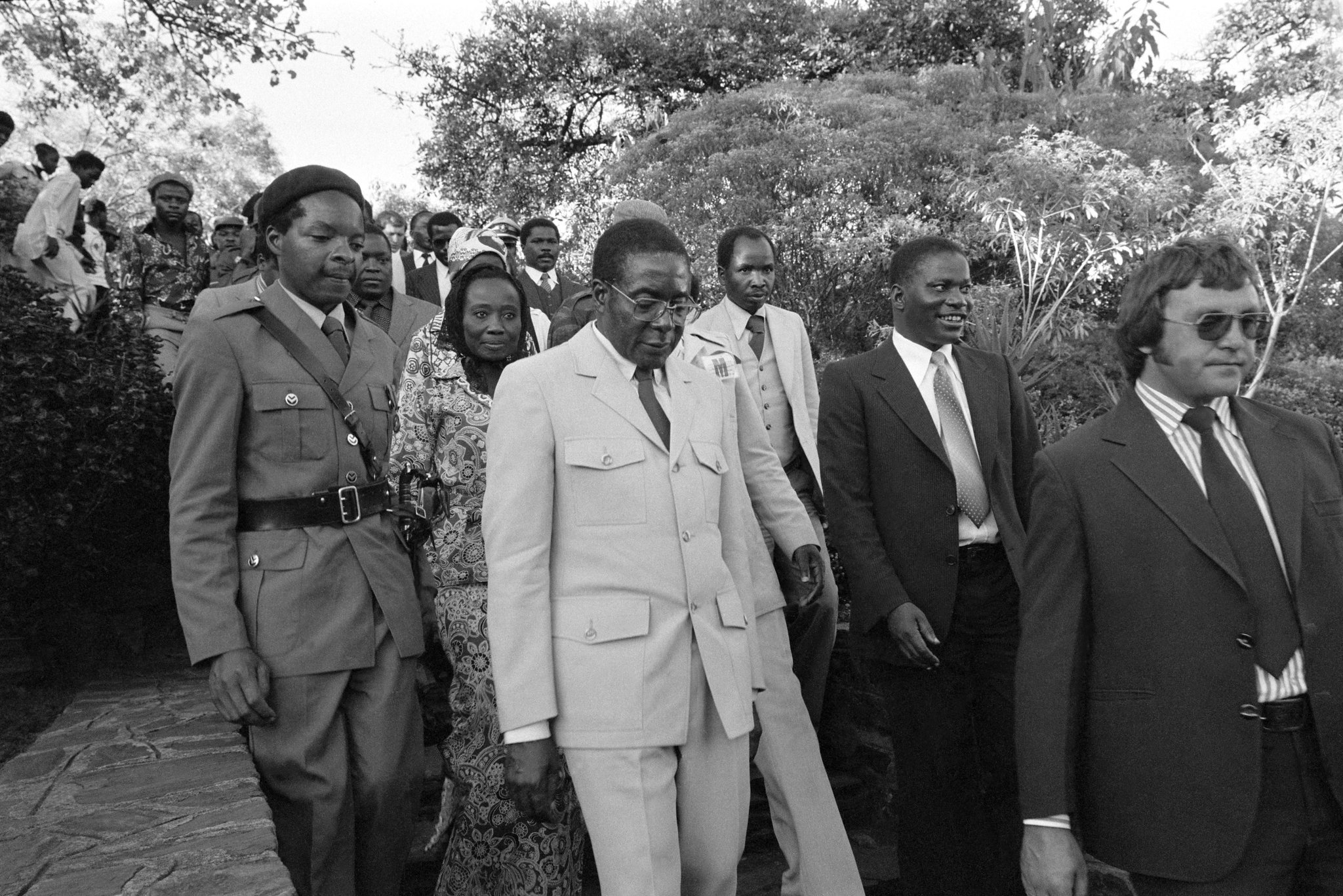

There were other omens that seemed to be recurring. Then, as it still is today, the seven-year guerrilla war against white minority rule was the font of legitimacy. On Jan. 27, 1980, when Mr. Mugabe returned from Mozambique in a tailored safari suit, he raised a clenched fist in victory. The crowd roared its approval.

Students at the University of Zimbabwe refused to take their exams on Monday unless Grace Mugabe’s doctorate was withdrawn. CreditZinyange Auntony/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

A few weeks later, I saw armored military vehicles in position at strategic intersections on my drive into work. There was much fevered speculation that the white-led Rhodesian Army, which did not consider itself to have lost the war in any military sense, was planning to intervene to reverse history. It never did. Last week, in an eerie reprise of those days, the Zimbabwean Army sent its troops and armored vehicles onto the same streets to begin Mr. Mugabe’s slow-motion ouster.

These days, too, the elite within the ZANU-PF party, which on Sunday dismissed Mr. Mugabe as its leader and expelled his wife, define their credentials by reference to the liberation struggle. The protests on Saturday in Harare were orchestrated by those claiming to be veterans of the liberation war. These were the same people who led the takeover of white-owned farms in 2000 after Mr. Mugabe felt the need to appease them.

Yet, the bulk of Zimbabweans are “born-frees” with no direct memory of a conflict that roiled the land. It was a brutal, sometimes dirty war, fought in skirmishes around white homesteads and in the remote bush, along dirt trails sown with land mines and in bloody raids by Rhodesian troops into neighboring countries where the guerrillas had their rear bases, notably Zambia and Mozambique.

Small wonder then that the guerrillas’ victory inspired such outpourings among those in whose name the war had been fought.

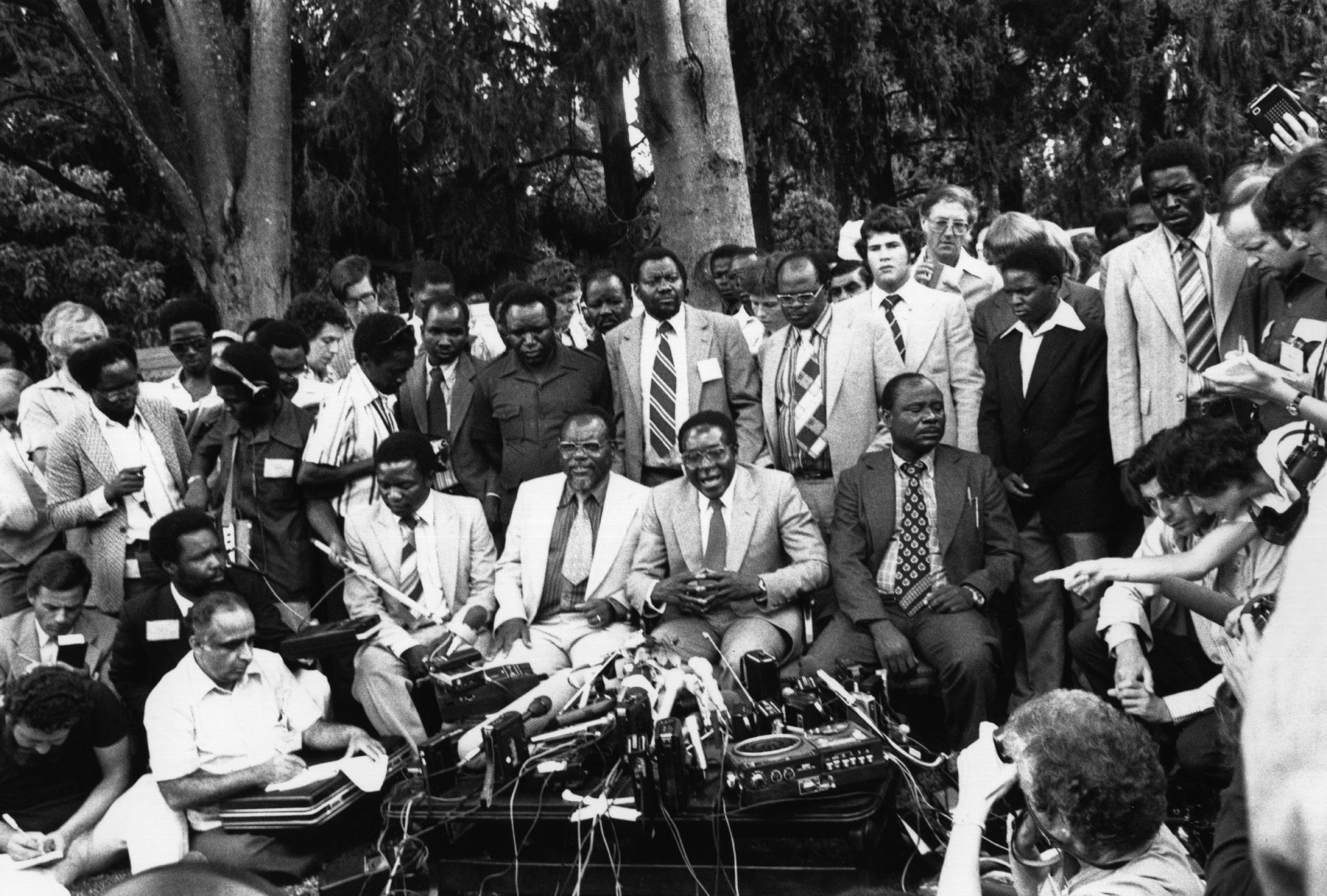

President-elect Robert Mugabe holding a news conference in his garden in Salisbury in March 1980.CreditKeystone, via Getty Images

Both men had grown up in a rough neighborhood. Both understood the rules that bind loyalty to largess. When he won power in 1980, Mr. Mugabe promised inclusiveness and pragmatism — pledges likely to be repeated by Mr. Mnangagwa.

Both men were part of the network of patronage that has cemented the ZANU-PF elite in power. When Mr. Mnangagwa was chosen on Sunday as the party’s new leader, some outsiders may have been reminded of an old Sicilian adage coined by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa: Everything must change so that nothing will change.

“The ousting of Mugabe,” Jason Burke wrote in The Observer on Sunday, “was a redistribution of power within the ruling elite of Zimbabwe, not a people’s revolution.”

But there are differences. Mr. Mugabe took over a viable economy and infrastructure. White-owned farms produced crops that fed the region and tobacco that earned foreign currency. Smooth roads unfurled across the land.

Mr. Mnangagwa, by contrast, will inherit a husk. And unlike the tens of thousands of Zimbabweans who greeted Mr. Mugabe in 1980, their descendants in the streets of Harare on Saturday may well feel that the last thing they want in a post-Mugabe era is for history to repeat itself.

COMMENTS

Interesting commentary. My observations include; firstly, the recorded number of Matabele deaths due to the 5th Brigade is recorded at over 20,000. Secondly, the transfer of power from Ian smith to Robert Mugabe was not orchestrates within the boundaruea of Zimbabwe; this transition has…..