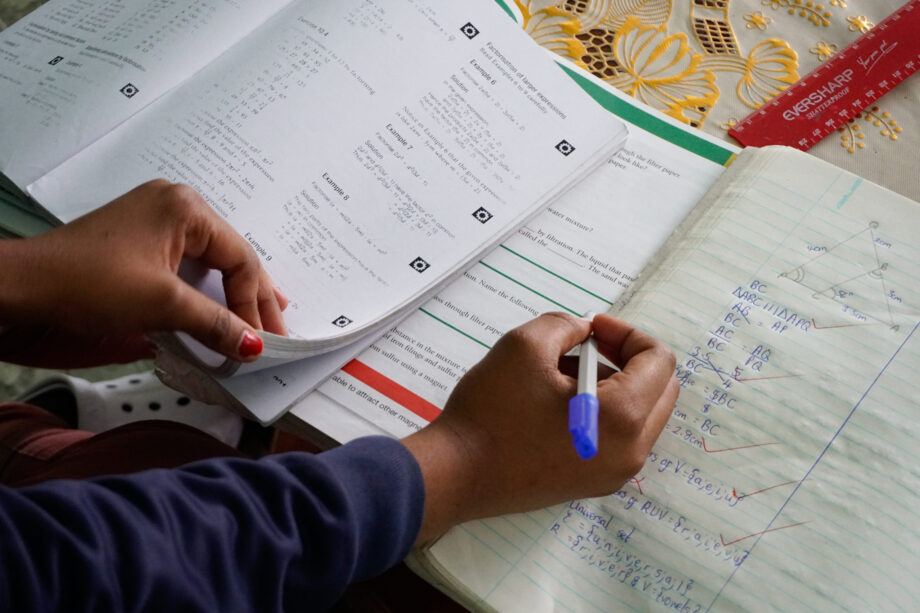

The country’s economic turmoil has led thousands of teachers to quit. Students don’t have that option.

Source: A Teacher Exodus Threatens the Future of Zimbabwe’s Education System

ILLUSTRATION BY WYNONA MUTISI

HARARE, ZIMBABWE — Kudzai Chideme, 42, stepped into the teaching profession after completing her diploma in marketing and failing to secure a job in the private sector. It was 2008. At the time, finding work in public education was relatively easy, but Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation had led to a severe devaluation of teacher salaries.

Chideme recounts how her first monthly salary amounted to the equivalent of about 15 United States dollars, not enough to afford groceries in the rural community 143 kilometers (89 miles) west of Harare where she lived and worked. Her first assignment was teaching geography and Shona, one of Zimbabwe’s official languages, in secondary school. “Things were really bad,” she says. “I remember with my first lump-sum salary [equal to three months’ salary], I was only able to buy a reed mat and clay pot.”

A glimmer of hope emerged a year later when, in 2009, the government dollarized the economy to bring financial stability to the country.

Civil servants’ wages were gradually reviewed and increased. By 2013, Chideme’s salary was bumped to 540 US dollars (3.3 million Zimbabwean dollars) a month. Together with her husband, who is also a secondary school teacher, she managed to buy a piece of land in Harare, where they built a three-bedroom cottage. The couple could even afford a live-in maid to help them take care of their two children. For the first time, Chideme could afford a comfortable lifestyle, but it didn’t last.

In an effort to stabilize the exchange rates and manage the country’s liquidity challenges, Zimbabwe reverted to using the local currency in 2019. That year, due to a loss of currency value, teachers’ salaries plunged. After the government introduced the so-called “cushioning allowances” to civil servants — a measure to protect public sector employees from hyperinflation — Chideme’s salary and that of her husband fluctuated around 280 US dollars (1.7 million Zimbabwean dollars) a month. The comfort they’d previously enjoyed vanished. “I had no peace of mind after getting paid,” she says. “I survived like someone who was not going to work.”

In May 2023, Chideme resolved to quit her job and leave her husband and children, including the latest addition to her family, a newborn, and migrated to the United Kingdom to work as an adult care worker. “It was a very difficult and horrid experience for me to leave my small baby,” she says. “It still pains me, but I had no option. I told myself that the sacrifice is worth it.”

Chideme hasn’t been the only teacher in her school to quit because she couldn’t make ends meet. Out of 38 teachers who worked at her public school in Harare, six resigned in the last year.

It is a nationwide pattern. According to the latest available data, from a report by the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education, in 2019, 826 teachers in Zimbabwe resigned, out of a total of 7,307 who stopped working in the school system for various reasons, including retirement and discharge. Education experts say that teachers’ resignations are driven by salary erosion and that the exodus is showing no signs of slowing down, with some teachers leaving for other professions and some for other countries.

Raymond Majongwe, secretary general of the Progressive Teachers Union of Zimbabwe (PTUZ), estimates that in the last year, 20,000 teachers have quit their jobs for other professions while remaining in the country. “Some have joined private organizations and others have been taken up in their family businesses,” Majongwe says, adding that many are leaving the country entirely.

“As far as the PTUZ statistics are concerned, between 2022 and 2023, we lost between 1,000 and 1,800 teachers who left the union for prospects in various countries,” he says.

Obert Masaraure, president of the Amalgamated Rural Teachers Union of Zimbabwe, says that a survey his union conducted between October 2022 and October 2023 revealed that about 4,000 teachers leave the country annually.

Global Press Journal was not able to independently verify the data shared by the two unions.

“Teachers are leaving in droves,” Masaraure says. “Those who are still in Zimbabwe are desperately searching for exit routes.”

The monthly starting salary for public school teachers is currently about 1,003,700 Zimbabwean dollars (164 US dollars) plus a monthly US dollar allowance all civil servants receive. In July 2023, the government increased the civil servant allowance from 250 to 300 US dollars, but teachers say it’s still not enough to meet their basic needs. The cost of a family basket of six — which refers to monthly expenses for groceries and utilities, as well as education and health care — stood at 540 US dollars as of July 31, 2023, according to the Consumer Council of Zimbabwe. The Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education did not reply to Global Press Journal’s request for comment.

The exodus of teachers is adding to an existing shortage. According to the education statistics report published by the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education, Zimbabwe needs 197,000 teachers to meet its workforce demand.

Experts say the current teacher shortage has built up over the last decade and a half. According to a 2017 South African Journal of Education article, Zimbabwean teachers began migrating abroad to escape the poor conditions that prevailed in the country during the early 2000s, which included economic and political uncertainty and hyperinflation. Over 35,000 teachers had left Zimbabwe by 2009, primarily for Botswana, South Africa and the United Kingdom.

“Educators don’t necessarily go back to the teaching profession as they migrate to other countries,” says Sifiso Ndlovu, chief executive officer of the Zimbabwe Teachers Association, one of the main teachers’ unions in Zimbabwe. While it’s more difficult to find employment in education for those who move to Europe, some who relocate to other African countries can find higher-paying jobs as teachers.

Rose, who asked to use only her first name for fear of stigma, migrated to Mozambique in September 2022 for a teaching opportunity. Her salary is now 1,100 US dollars (6.8 million Zimbabwean dollars), while in Zimbabwe, as a secondary school math teacher in the capital, Harare, she was making about 235 US dollars (1.4 million Zimbabwean dollars) a month. “I could not afford to buy professional clothing in a proper shop. [I] relied on secondhand clothes, like someone who was not a professional,” she says, explaining that she’s now earning nearly fivefold what she used to earn. “I have managed to make savings.”

While Rose says she’s content with her choice to leave, she’s aware that her departure has created problems for her former colleagues.

A 41-year-old teacher who worked with Rose at her previous school in Zimbabwe, and who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution, says teacher migration greatly affects those who stay. When Rose left, the remaining teachers had to cover her classes because it took months to find a replacement. “If you had three classes, you ended up with eight classes, which is a huge load,” Rose’s former colleague says.

According to the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education 2021 Annual Statistics Report, the teacher-to-learner ratio in Zimbabwe’s secondary schools stood at one teacher for every 25 students, which is within the thresholds recommended by the ministry. But teachers say the ratio is often higher.

“In government schools, teacher-pupil ratio does not exist. It has always been high,” says the 41-year-old teacher, who has three classes with an average of 45 students in each.

Many believe the teachers’ exodus has made the situation worse and is now affecting the quality of education in the country.

Eurita Nyamanhare, the director of community service in the office of the vice chancellor at Zimbabwe Open University, who has spent 40 years working in the education system, says teacher migration compromises students’ education. “Once the [teacher] is not there, it means the learning aims and goals will never be fulfilled as expected,” she says.

Nyamanhare adds that when a student is left without a teacher, they lose focus and interest in learning.

This is true for Chloe, 15, Rose’s former student, who asked to be identified by her first name for fear of reprisal. She says spending the whole term without a math teacher last year affected her grades.

“I was not getting the marks I expected. My grades decreased. I got scolding at home for failing. The teachers who assisted us with math only came for two days during the term because they were also tied up with their own classes,” she says.

Chloe says that during their math lessons, she and her classmates chatted and basked in the sun because they had no guidance. This year, her English teacher left, too, and was replaced after almost a month.

Chloe’s mother says she has seen the impact of teacher migration on her child’s performance and that it’s jeopardizing her future. Chloe dreams of becoming a doctor, but her secondary school grades will determine her medical school acceptance. “I had to look for money for extra lessons, which is expensive because you pay at least 10 dollars per subject, but it’s a sacrifice I must make to help improve her grades,” Chloe’s mother says.

According to Macrotrends, an online research platform, Zimbabwe’s adult literacy rate is 89%, one of the highest in Africa. But experts say Zimbabwe’s ranking may be compromised if skilled teachers continue to leave the profession.

“In the long term, it will impact education development in our country,” Ndlovu says. “Not only that, but our learners will also become less competitive in the world.”

For Chideme, though, her move has changed her life.

“I can now send enough for my children’s upkeep,” she says. “I recently afforded to pay for my child’s trip, something which a teacher in Zimbabwe is unable to do.”

Gamuchirai Masiyiwa is a Global Press Journal reporter based in Harare, Zimbabwe.

Global Press Journal is an award-winning international non-profit news publication that employs local women reporters in more than 40 independent news bureaus across Africa, Asia and Latin America.

COMMENTS