Illustrative image: Zunaid Moti and Kuda Tagwireyi (Photos: Supplied | Jekesai Njikizana / AFP / Getty Images | Shiraaz Mohamed)

Leaked documents show how the Moti Group became enmeshed in huge, possibly illicit, money-moving networks in South Africa and Zimbabwe. Seemingly artificial loans and investments were used to move hundreds of millions of rands across borders and through Moti’s companies. In Zimbabwe, at least some of the cash allegedly ended up with the country’s president and vice president.

Zunaid Moti’s business empire worked with alleged underground financial operators channelling vast sums through his mining and property companies using complex smoke-and-mirrors transactions.

In less than a year, well over R2-billion moved through these mechanisms – funds mostly derived from investments by Moti’s former partner in Zimbabwe, the politically connected Kudakwashe “Kuda” Tagwirei.

AmaBhungane has been able to tie Moti to two separate money-moving operations using extensive documentation in the #MotiFiles leak and another unexpected source – the wreckage of the doomed VBS Mutual Bank.

Despite its complexity, the picture ultimately boils down to this: vast amounts of money were channelled from Moti’s African Chrome Fields (ACF) to a range of mysterious Zimbabwean entities (some linked to the country’s political leadership) under the guise of loans to a different Zimbabwean business partner, Patrick Chinondo.

At the same time, across the border, a mountain of money appeared in South Africa, flowing to Moti Group companies under the guise of “property loans” that, on the surface, were unconnected to the Zimbabwean transactions.

We will see how VBS became a bridge between the different role players in the two countries before the bank imploded in early 2018, suggesting these Moti transactions in Zimbabwe and South Africa were two sides of the same coin.

There is reason to suspect they formed a single scheme aimed, at the very least, at improperly exporting capital from Zimbabwe. Moti denies and contests the basis for this suspicion.

In Part One of this investigation, we deal with the first operation, based in Zimbabwe, which saw Moti’s ACF distribute the largesse received from prominent Zanu-PF benefactor Tagwirei.

In Part Two we will cast an eye across the border to South Africa where an operator called “Joe Dollars” was seemingly enlisted to route hundreds of millions of rands into Moti’s labyrinthine group of companies.

And while Moti has defended these manoeuvres as legitimate and separate business deals, he faces one awkward hurdle: despite copious documentation, the partners he allegedly transacted with vociferously deny key aspects of his version.

It is important to try to establish the truth because, as the Al-Jazeera #GoldMafia series has documented, Zimbabwe has become a hub for illicit money flows, with implications for citizens, businesses and governments throughout the region.

To better understand all this we need to take a step back – and look at how Moti may have found himself needing to get piles of cash out of Zimbabwe, the country whose development he has long claimed to be deeply invested in.

Step One: ‘A fuck-ton of money’

Moti made his grand entrance into Zimbabwe in 2014 with what would become his flagship mining venture, ACF.

From the get-go, the company was immersed in Zimbabwean politics, bringing on board a partner company owned by the country’s military and hiring then-vice president Emmerson Mnangagwa’s son as a “consultant”.

The money-moving operation, as far as amaBhungane can establish, started in late 2017 in the middle of the coup that toppled Robert Mugabe.

As a political storm was gathering, Moti forged an alliance with Kuda Tagwirei, a businessman with well-documented ties to Zanu-PF as well as to Mugabe’s challenger and the current president, Emmerson Mnangagwa.

Tagwirei is a fuel tycoon who was the controlling shareholder of the lucrative Zimbabwe operations of Trafigura, the global commodity trading behemoth which has long had an iron grip on parts of the country’s energy sector.

He has enjoyed several concessions from the state and has lately found himself on US and UK sanctions lists.

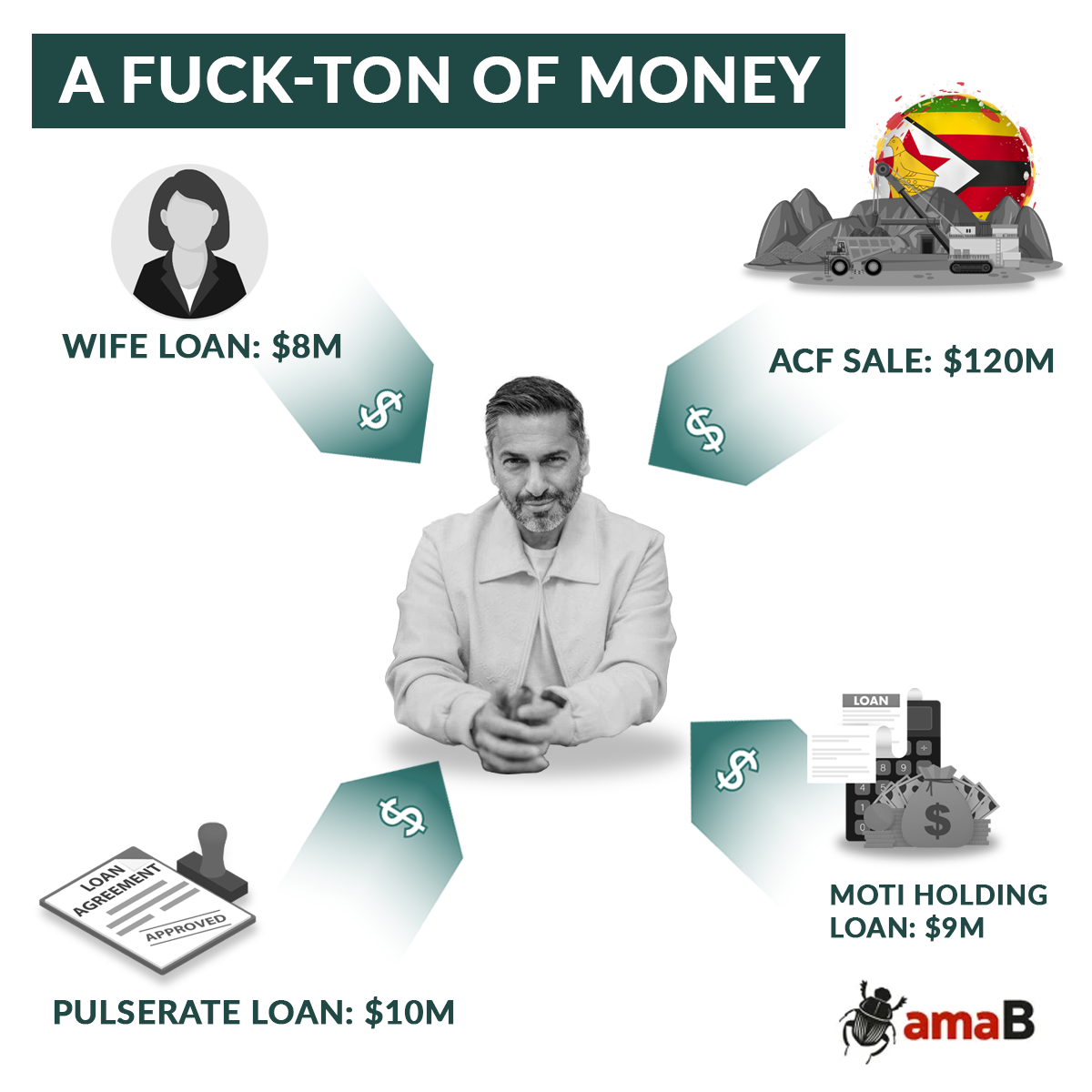

Moti’s relationship with Kuda blossomed rapidly into enormous infusions of cash.

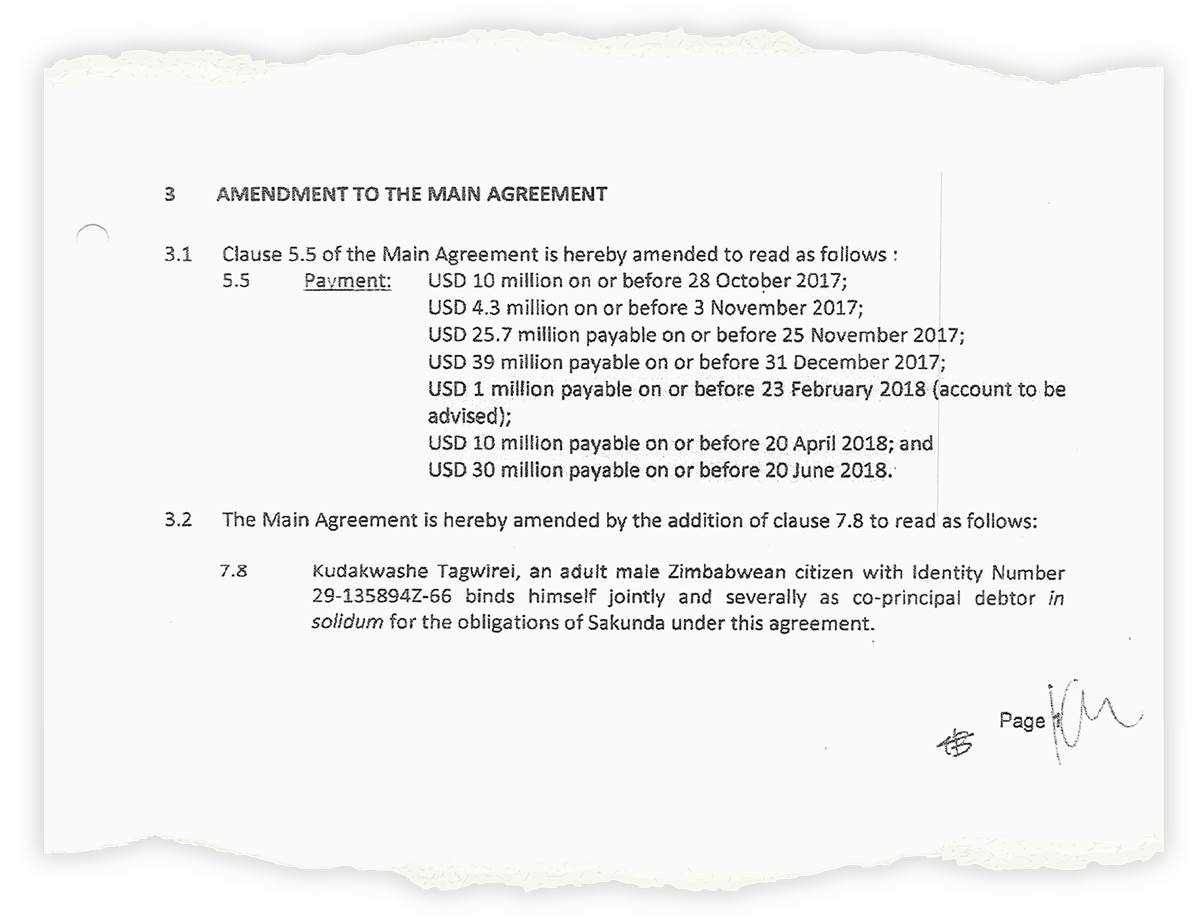

Barely a month after their first introduction, in the middle of the coup, Moti signed a transformative deal with Tagwirei – the sale of 30% of ACF for $120-million (then R1.7-billion).

The full mechanics of the deal were more complicated.

The seller of the 30% was technically a company called Spincash owned by local Zimbabwean Moti allies (with a minority stake held by an associate of Vice President Constantino Chiwenga).

Moti denies he or his family had any financial interest in Spincash and said it was referred to as part of the Moti Group merely “for ease of reference”.

In response to a claim that he exercised “effective control” over Spincash, he told us, “Alleged ‘effective control’ of anything can also not automatically be equated to a financial interest therein. It is very much possible to ‘control’ something without having any interest in it.”

It was nonetheless ACF rather than Spincash that received the payment from Tagwirei. According to Moti, this is because it did not have its own bank account.

“Spincash, which did not operate a bank account, requested that ACF receive the funds on their behalf, and ACF obliged. No more, no less. There is nothing ‘improbable’ about such an arrangement – Spincash ultimately still received what was due to it in terms of the transaction.”

But the end result was that Moti’s ACF was suddenly on the receiving end of millions of dollars, spread over several months.

There was more.

Among the leaked #MotiFiles are two loan agreements from early 2018 whereby Tagwirei made available $9-million to Moti Holdings, a group company in Dubai, and $8-million to Moti’s wife (about R200-million altogether).

Both loan agreements vaguely record that the money was for “investments in art, investment cars and … equity investments in private or listed companies”.

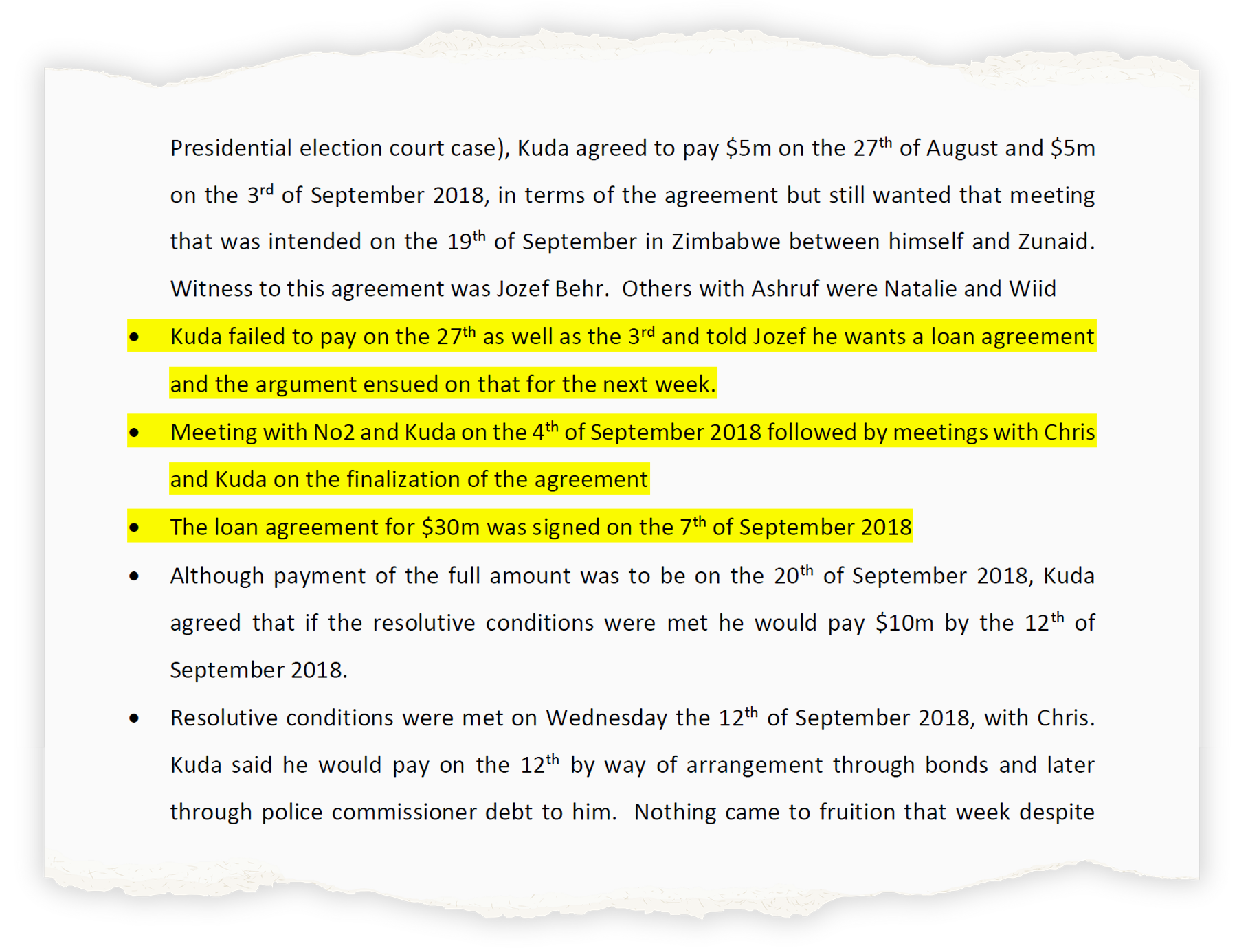

In September 2018 Tagwirei extended another loan for 30-million RTGS, technically $10-million in the “digital” Zimbabwean currency at the time, to one of Moti’s aspiring mining companies, Pulserate Investments.

This loan, judging by another document in the #MotiFiles, a briefing to Moti during his incarceration in Germany, appears to have been facilitated in part by Zimbabwe’s post-coup vice president Constantino Chiwenga, often referred to as “No. 2” in internal Moti Group correspondence.

Moti told us the loans to Moti Holdings and his wife were never fully utilised and in any case were fully paid back.

All of this nonetheless set the scene for Moti and his companies becoming progressively larger recipients of cash from Tagwirei.

In a leaked recording of a 2022 meeting of top Moti Group executives, in-house legal boss Natalie Graaff pointed out that they could not practically extricate themselves from Tagwirei because it would be too expensive. By this time the association with Tagwirei had become something of a liability due to sanctions imposed on him.

“How do you get him out now? You’re going to have to buy him out. It’s a lot of money. He gave us a fuck-ton of money,” said Graaff.

More important however is what Moti seemingly did with that “fuck-ton” of money.

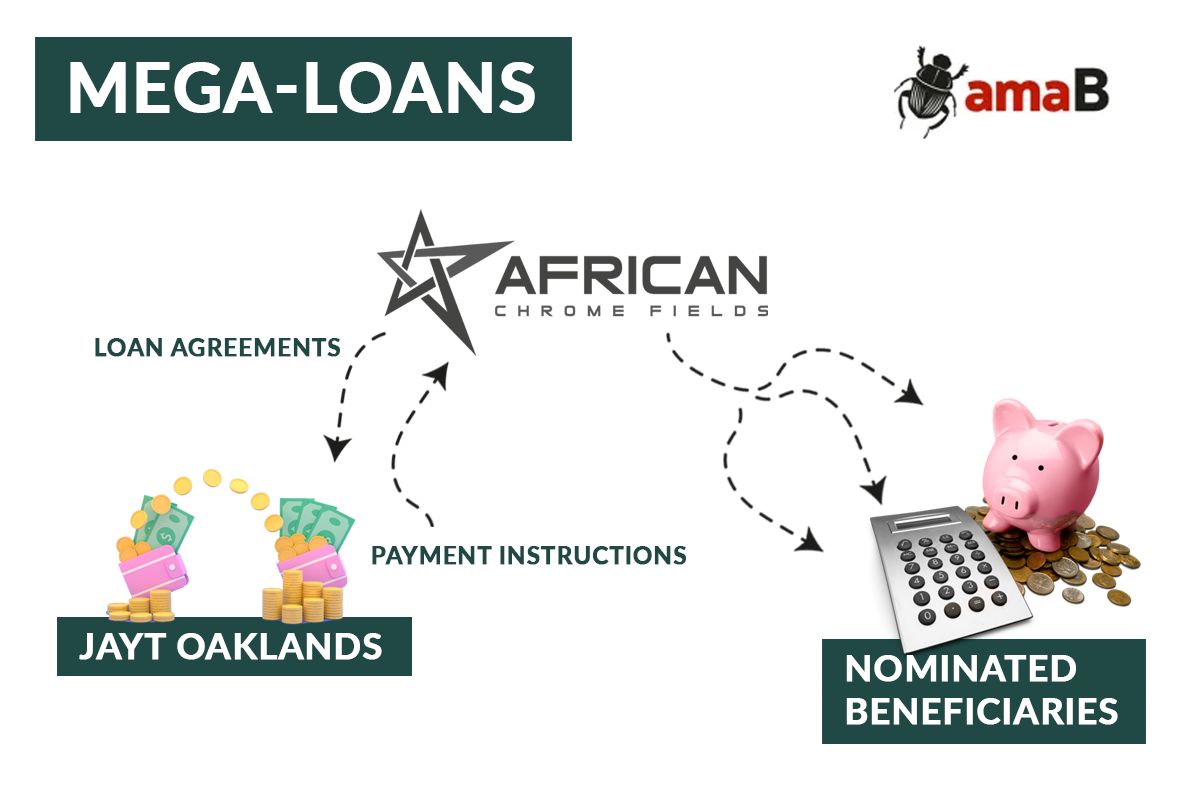

Step Two: Zim mega-loans and multi-payments

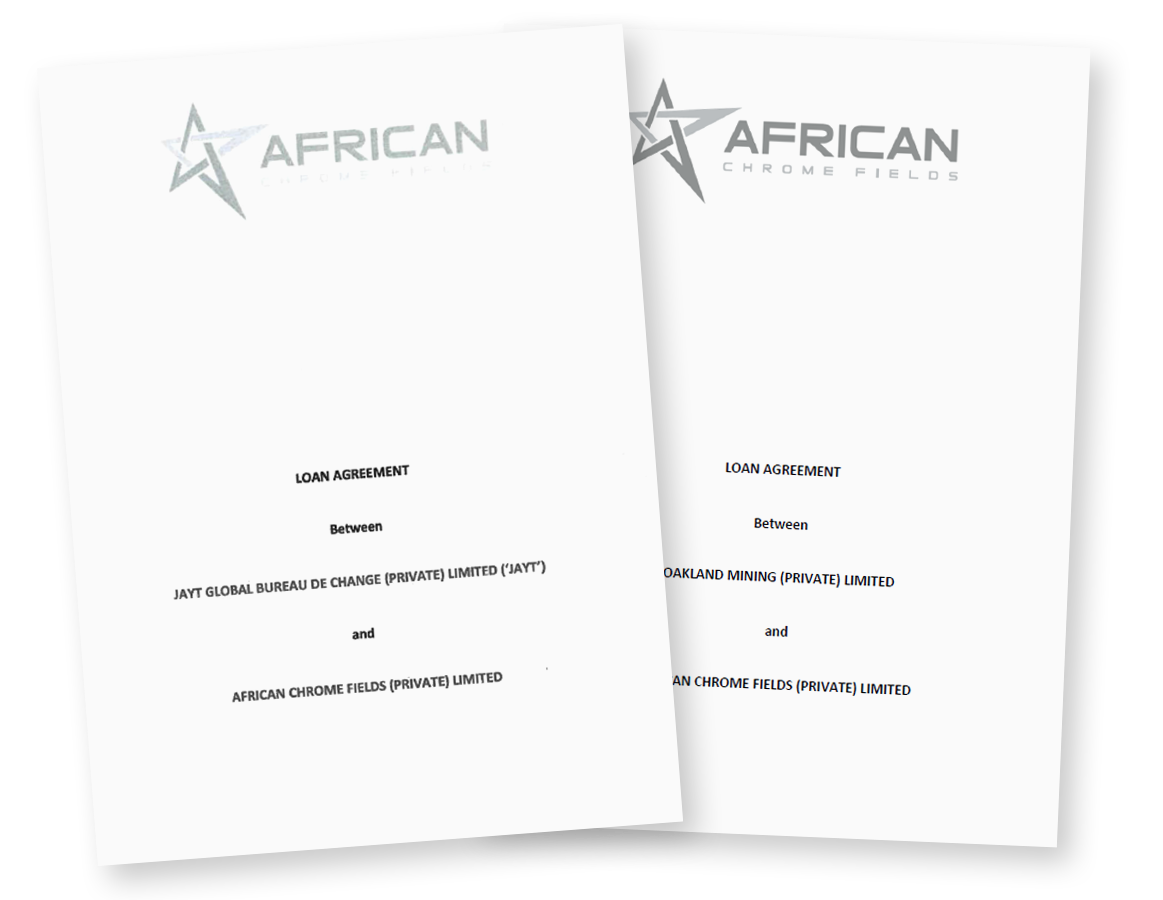

Almost immediately after signing the $120-million deal with Tagwirei in November 2017, Moti’s ACF signed a separate loan agreement with JayT Global Bureau du Change, a company belonging to one Patrick Chinondo – a Zimbabwean partner to Moti in this and other enterprises.

The loan was huge: After several amendments over the following months Moti offered JayT at least $75-million (roughly R1-billion) in total.

In June 2018 this arrangement was succeeded by a practically identical new loan between ACF and another Chinondo company called Oakland Mining.

Asked about these loans, the Moti Group said that they were part of a strategy to safeguard the value of the money received from the ACF-Tagwirei deal by sinking it into other investments via JayT and Oaklands.

At the time, Zimbabwe had adopted the US dollar but was experiencing an acute shortage of the currency. This led to a relative devaluation of electronic account balances (which in practice could not be withdrawn).

These deals are in ACF’s name despite the money allegedly belonging to Spincash, which is not mentioned in the loan agreements at all.

The arrangement with JayT and then Oakland was also extremely peculiar.

Instead of ACF actually advancing money to these borrowers, it would instead receive a constant torrent of “payment instructions” from the Chinondo companies.

These would tell ACF to rather pay money directly to other third parties.

Through this system, Moti’s ACF made 505 payments to dozens of different recipients between November 2017 and September 2018. The grand total: an astonishing $130-million (roughly R2-billion at the time).

Red flags

There is reason to interrogate Moti’s claim that all this was a legitimate scheme to protect the value of his company bank balances.

First and foremost, the owner of both JayT and Oakland, Patrick Chinondo, outright denies most of these payments ever happened.

In his version, he borrowed “small amounts”, not millions of dollars, and stopped issuing payment directions long before most of the payments were made in his name by Moti’s ACF.

This is despite the loan agreements bearing his signature explicitly referring to vast sums of US dollars and the payment instructions as well as ACF records showing the payments going through.

Confronted with this evidence, Chinondo responded that “the so-called evidence … could have been tampered, fabricated, edited and doctored documents to meet the narrative you seek to establish”.

Asked about the loan agreements, Moti in contrast never challenged their existence or the quantum.

Both versions cannot be true.

Irrespective, the transactions themselves are problematic.

For one thing, some of the money flowing out of ACF seemingly lined the pockets of senior politicians including Zimbabwe’s president, vice president and the then minister of communication.

A president’s farm, a ‘frontman’ and a minister

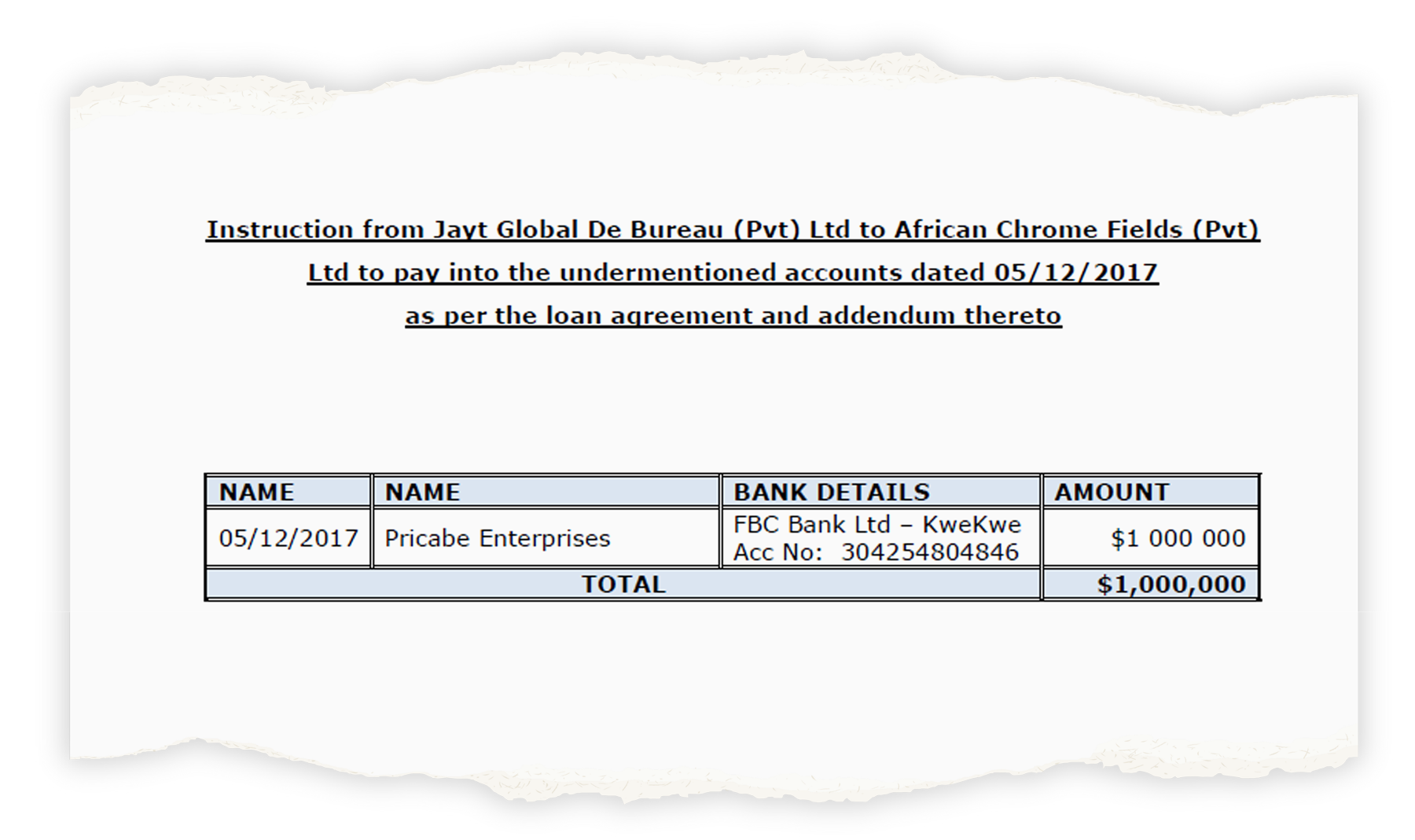

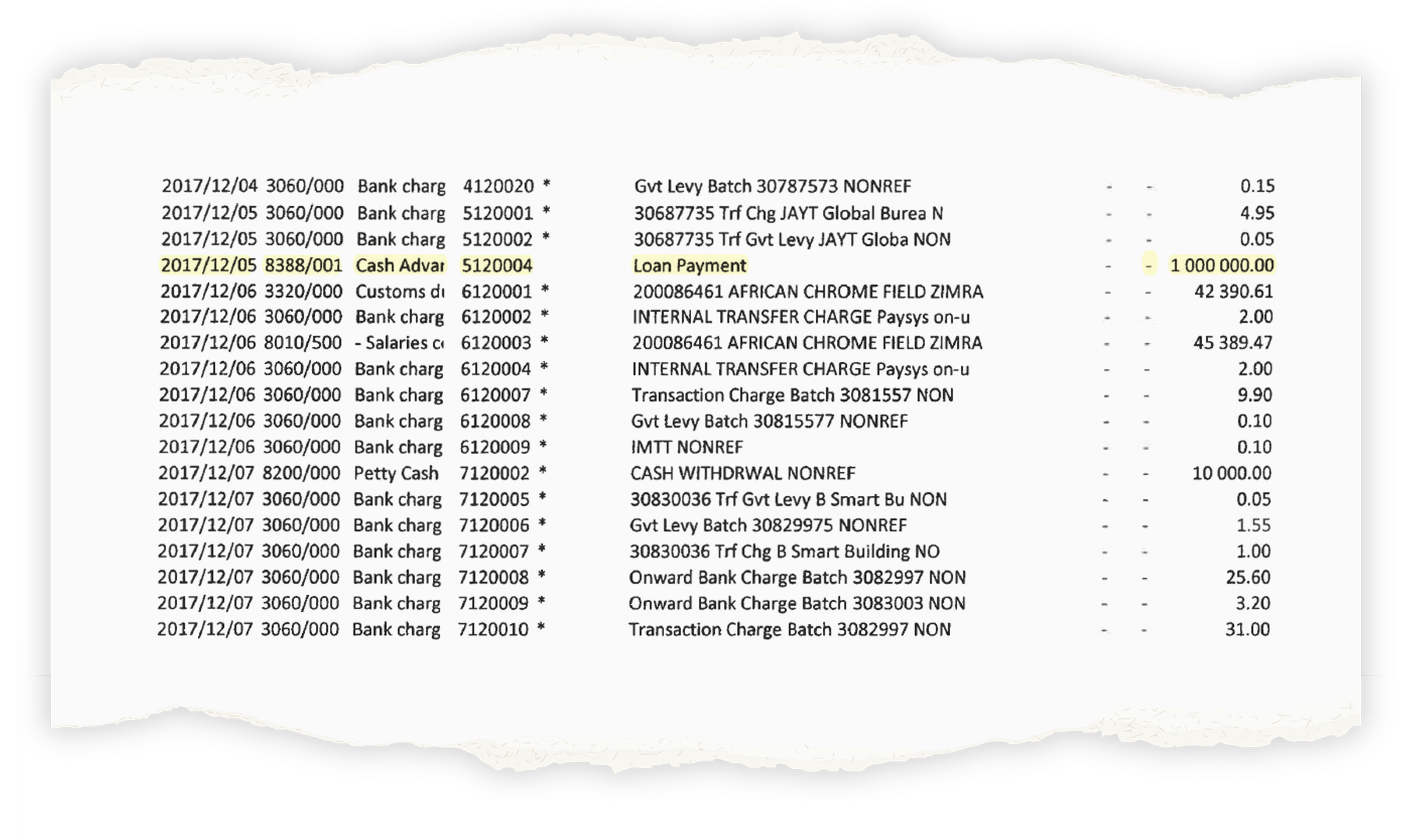

One $1-million payment ACF made soon after the coup, on 5 December 2017, on JayT’s instruction, was to a company called Pricabe Enterprises. According to Zimbabwean media, this is the holding company for President Mnangagwa’s farm.

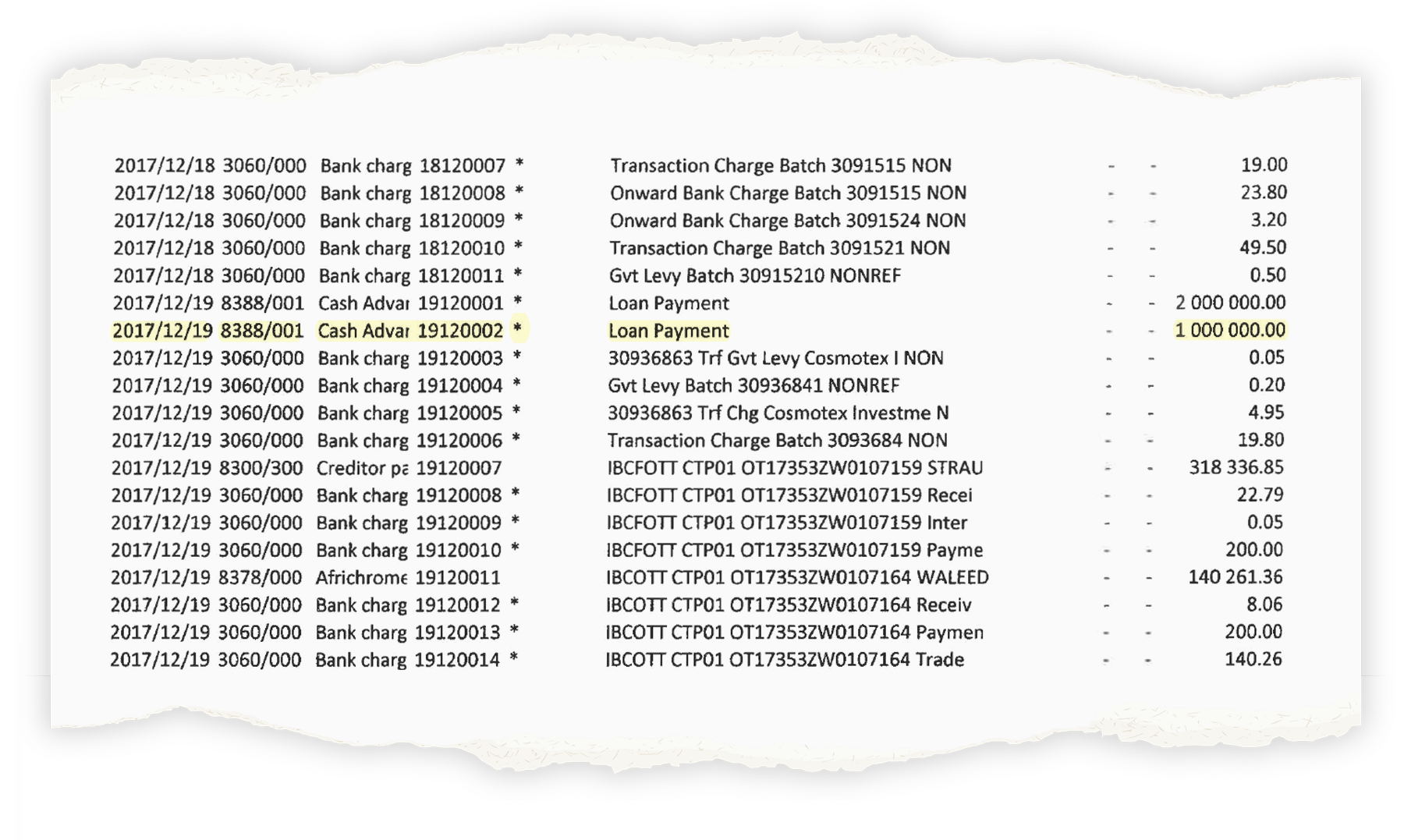

ACF’s cash accounts, also contained in the #MotiFiles leak, duly show the money being paid out under the guise of a “loan payment”.

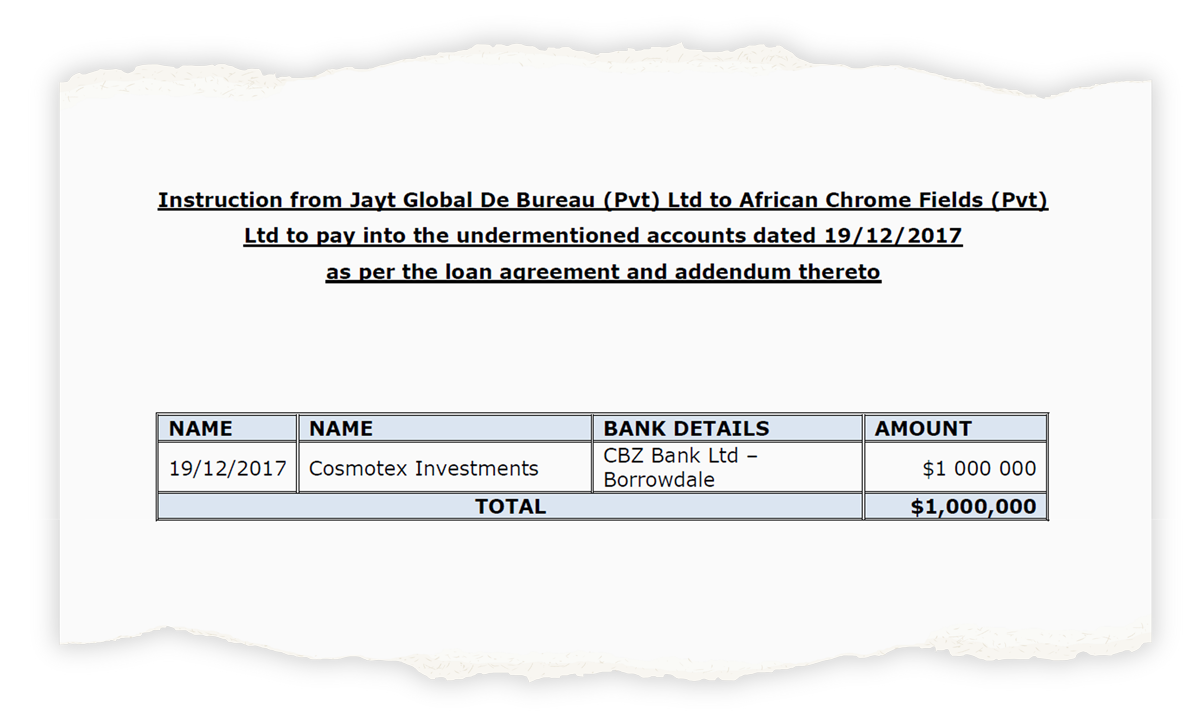

Another notable recipient was Cosmotex Investments, a company owned by Zimbabwean businessman Lishon Chipango. Chipango is, according to Zimbabwean sources, a proxy for the military commander who became vice president after the coup, Constantino Chiwenga. This company received $1-million in December 2017, according to the ACF accounts.

And money also went to the then minister of communications, a significant Zanu-PF veteran.

In other words, in the weeks following Zimbabwe’s coup, Moti’s ACF made payments on JayT’s instructions totalling some R26-million to the benefit of key members of the country’s new leadership who held the fate of his most prized asset, his chrome mine, in their hands – though this was allegedly on the instruction of Chinondo.

Moti told us, “I reject all allegations that ACF was involved in money laundering or corruption. All its dealings (even with prominent political figures) were correct and in the ordinary course of business.”

Apart from politicians, more of the ACF payments made on Chinondo’s orders raise questions.

Mystery accounts

The largest chunk of the cash flowing out of ACF, just shy of $60-million, apparently did go to entities belonging to Chinondo himself – JayT, Oakland Mining and Oakland Global Investments. It is, however, unlikely that this was the final destination – which we will get to shortly.

If we strip out payments to Chinondo, the rest of the money flowing from ACF according to the “payment instructions” largely went to only three recipients who between November 2017 and September 2018 received 279 payments totalling $50-million (roughly R650-million).

The three companies receiving most of this money were called Retoch Investments, Ask and Get It and Kunjani Duty Free Investments.

All three companies have missing company records at the Zimbabwean Registrar of Companies and Chinondo denies any knowledge of them. It is not known who controlled them or what the money was for. However, watch this space.

To sum up, the politically connected Zimbabwean tycoon Tagwirei provides Moti’s ACF with hundreds of millions of rands in the aftermath of the 2017 coup. ACF in turn enters into loan agreements also worth hundreds of millions but which the supposed borrower denies. ACF nonetheless pays the millions, apparently on the borrower’s instructions, to opaque recipients about whom no information is available, as well as a portion for the seeming benefit of top Zimbabwean politicians.

Step Three: VBS and Joe Dollars – a preview

VBS Mutual Bank collapsed in March 2018 after being pillaged by its management.

In a separate exposé today, we reveal how the bank also hosted an enormous hawala system used by many Zimbabwean businesses and individuals, seemingly to circumvent exchange controls.

The system seemingly involved illicit gold smuggling and the notorious Macmillan family, which has recently been implicated in money laundering by Al Jazeera in its Gold Mafia series.

It appears that VBS also played a role in the movement of funds by the Moti Group and its partners.

Although Moti denies all knowledge of the VBS system, bank records show that it was used to pay millions to his South African companies, seemingly via Chinondo and the aforementioned Joe Dollars.

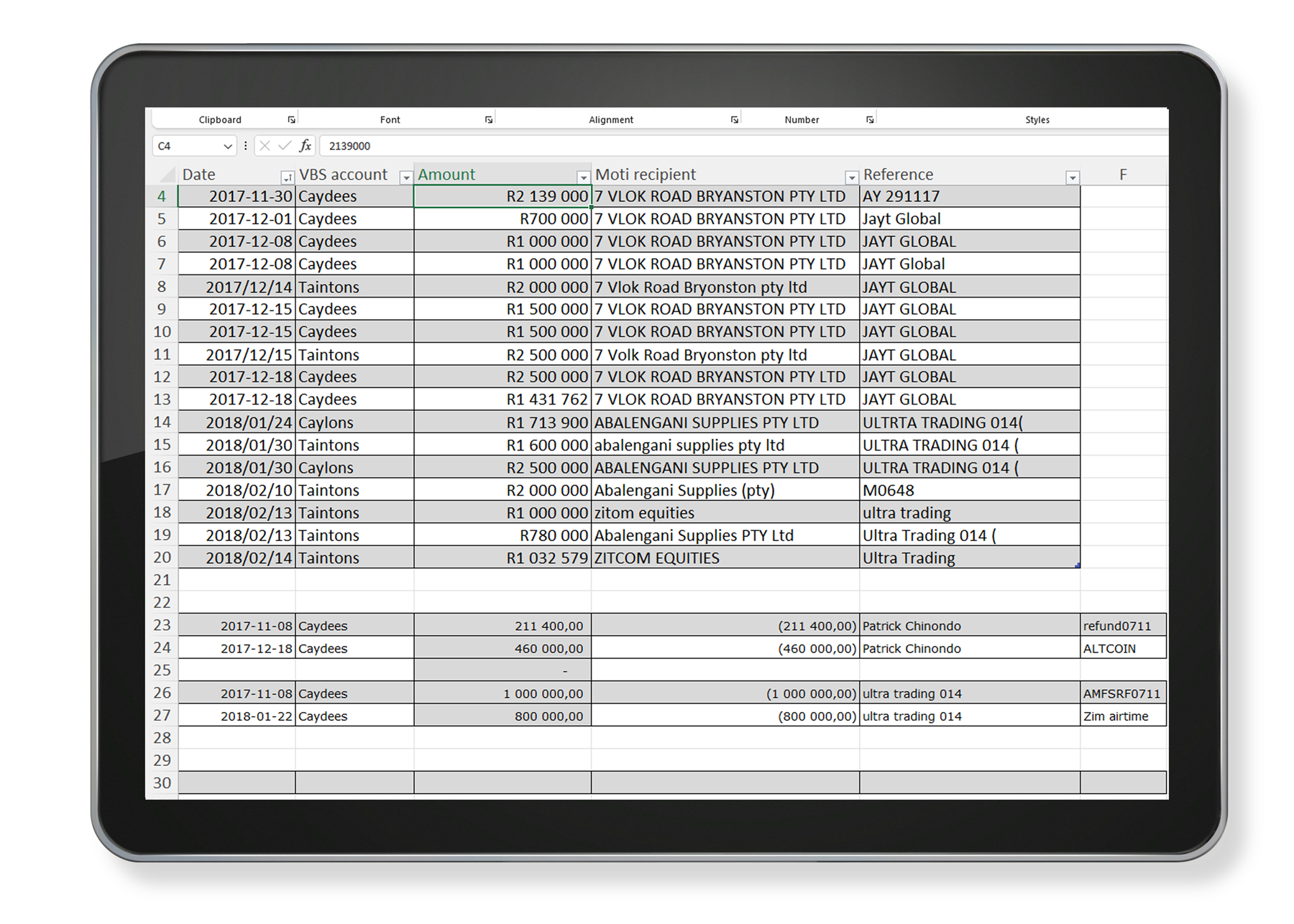

Between 30 November and 18 December 2017 one of the VBS accounts – Caydees Imports and Exports – made eight payments to 7 Vlok Road Bryanston (a Moti property holding company) totalling just shy of R12-million.

Once again, this flow of funds followed hot on the heels of the coup and the first infusion of Kudwirei’s cash.

Most of these payments reference “JayT Global”. This suggests some of the money that went from ACF to Chinondo in fact then somehow went back to the Moti Group in South Africa in a way that cut straight through Zimbabwe’s desperate exchange control regime, which has been trying to keep scarce dollars in the country.

Upon inspection, it is clear that Moti companies also received VBS money tied to someone else besides JayT (Chinondo).

Further payments to Moti companies using VBS brought the total to R26-million spread across less than three months.

Several payments reference “Ultra Trading 014” and evidence suggests that there was another hidden hand in these payments made through VBS and additional channels – long-time Moti associate Joe Dollars.

Moti told us, “I have no knowledge or context to the name ‘Caydees Import and Export’ and have not dealt with them in any manner… I have not obtained bank statements of other entities (illegally or otherwise), so I cannot comment on the content thereof. The only facts that I know is that 7 Vlok Road Bryanston received funds into its bank account under the Ultra transactions.

“Our dealings with Ultra were indeed explained to our bankers in detail at the time, and they raised no objection thereto. I fail to see why, if they were satisfied, you see fit to question these transactions.” DM