African wild dog pups are a dim black and look ancient, like old bronze, like the Capitoline Wolf

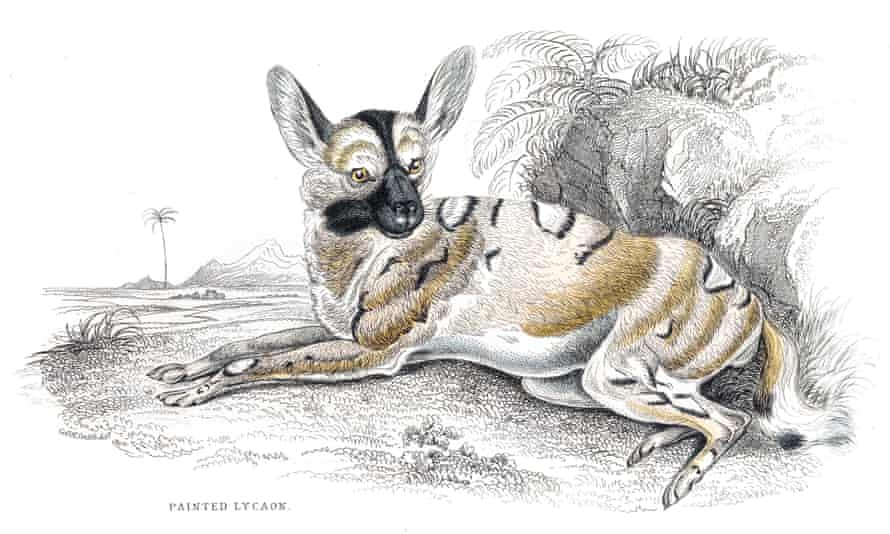

The African painted dog does not look much like this William Jardine engraving from 1840, but it does have very large ears. Photograph: THEPALMER/Getty Images

The African painted dog – also known as a wild dog or painted wolf – has ears that look as though they have been stitched together by a mad old toymaker. They are huge, bristly black disks – stretched upwards slightly and delicately pinned so that they form shallow bowls. At their bases are tufts of white bristles, for luck.

As a child in South Africa, I was forced more than once to watch – on a large pull-down projector screen in the school hall while it rained outside – Paljas, a uniquely, skin-crawlingly kitsch film set in a dusty railroad town that is visited by a travelling circus.

The wild dogs’ ears remind me of a scene where the clown, at night, pretends to be a hare, his hands the ears turning inwards and outwards. (I cannot find this scene on YouTube; it is possible that I invented it all those years ago while dissociating from my body, but here is a dramatic re-enactment of the film by high school students).

Painted dogs’ coats are an uncanny mix of sharp patterns and shaggy, blurry patches. Together these create the impression that the dogs are at once fast-moving and perfectly still. They have white-tipped tails, they have shiny black noses, they live in packs and sleep with their limbs resting on their siblings’ bodies.

Wild dogs vote by sneezing, deciding whether to hunt based on a “quorum” of achoos. When their leader – always female – dies, they vote for her successor with eerie whoops and hoots. They rarely fight and are particularly successful predators, gleefully ripping apart live smaller prey by each holding a limb and pulling in four directions.

The puppies are dim black and look ancient, like old bronze, like the Capitoline Wolf.

Wild dogs live in sub-Saharan Africa. In Southern Africa, the San tell a legend: moon declared that, just as he died and was reborn, people would be reborn. But hare would not believe this. Moon and hare fought – moon split hare’s lip, hare scratched moon’s surface – and moon took back his offer of rebirth. He also condemned hare to be forever on the run, chased by wild dogs.

I’ve seen wild dogs in Zimbabwe, at Mana Pools, where the dogs live in the shadow of the local elephants, who are famous for their habit of rocking their ponderous bodies on to their back legs to reach the tips of trees.

In a documentary about Mana’s wild dogs, David Attenborough narrates as the pups skitter back into their dens after watching a leaf-chewing elephant flump back down to earth. Later, the pack’s leader trips – running on what Natalie Angier has described as legs “like the sticks of a shadow puppet” – into the wide hole made in mud by an elephant’s foot and hardened in the sun. Her leg breaks, but the pack does not abandon her. “Painted wolves, perhaps more than any other animal, care for pack members who are old or injured,” says Attenborough. In other scenes, the dogs are shown from above, their thin bodies like stitches on the earth, shadows rising in trotting dog profile.

The painted dog diverged from other canids 1.7 million years ago and has four toes, compared to domestic dogs’ five. Nonetheless, I choose to believe that, as my uncle James says of his hounds (which have included an English bulldog named Sam Sam Sam Sam Sam Sam Sam): you can smell the world in a dog’s paw.

A recent study found that what makes domestic dogs affectionate, devoted and so entirely sweet – to any animal they’re raised with – is genes associated with a disorder that, in humans, causes “indiscriminate friendliness”.

Wild dogs reserve this love and devotion for each other.

I’m 22 in the Mana Pools reserve: In a patch of springy green plants lies a pack of painted dogs. From a game vehicle, a friend and I watch until the game ranger inexplicably encourages us to exit the vehicle, perform a poor excuse for a leopard crawl, and lie flat within a metre or so of the pack. They pay no attention to us – it is golden hour and the dogs take turns closing their eyes gently, tilting their big ears back slightly in contentment.

“The Nature of … ” is a column by Helen Sullivan dedicated to interesting animals, insects, plants and natural phenomena. Is there an intriguing creature or particularly lively plant you think would delight our readers? Let us know on Twitter @helenrsullivan or via email: helen.sullivan@theguardian.com

COMMENTS